Summary

Part One: Language and Archaeology

Chapter One: The Promise and Politics of the Mother Tongue

- The author is of the opinion that the PIEs (proto-Indo-Euros) homeland was in the steppes of Ukraine & Russia

- The PIEs of the steppes were responsible for domesticating the horse and grazing animals (sheep, cattle). They eventually acquired the wheel, allowing them to follow their herds anywhere using wagons to transport their belongings.

- this allowed the isolated peoples of Europe and China to become aware of each other’s existence

- Sir Willian Jones, in 1786, was the man responsible for discovering the similarities between Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, etc, and coming to the conclusion that they must have come from a common source - p. 7

- origin of the word “Aryan”- p. 9

- The authors of the oldest religious texts in Sanskrit and Persian, the Rig Veda and the Avesta, called themselves “aryans”

- These “aryans” lived in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India

- So technically speaking, the term “aryan” should only be applied to the “Indo-Iranian” branch of PIE

- Europeans started to use the term “aryan” to describe themselves as a superior race

- In the Rig Veda, there are passages that describe the aryans as being invaders who had conquered the land. This led to the mystery of where the “aryan” homeland is located

- Sir William Jones believed it to be Iran - p. 9

- many others started to argue that their own country was the true aryan homeland

- the mystery of the aryans was very politicized. Many tried to use this term to describe their own race as the supreme race. The Nazi’s even funded archaeological excavations to prove themselves as the aryans. - p. 10

- the connection between language and race is so loose that it’s practically non-existent. So to solve the PIE problem, you have to realize that the term Proto-Indo-Euro refers to a language family, not a race - p. 11

- In all Indo-European languages, speakers are forced to specify the tense of the action, and whether the actor is singular or plural. This is a common grammar point in all Indo-Euro languages. - p. 19

- on the other hand, languages in other family groups differ. Ex: in Hopi, tense and singular/plural is not important. Rather, you must specify whether you witnessed the event yourself, heard about it from someone else, or consider it to be an unchanging truth. In other words, Hopi grammar frames all descriptions of reality in terms of the source/reliability of their information - p. 19

Chapter Two: How to Reconstruct a Dead Language

- The most basic linguistic problem is to understand how language changes with time

- In general, a millennium is enough time for a language to change dramatically where you as a native speaker would have lots of difficulty to understand it from a millennia ago

- an example of English is provided on page 22

- even for us, reading Shakespeare can be quite difficult and he wrote 500 years ago

- 2 reasons why a language changes over time

- no two people speak the same language exactly alike

- most people meet lots of people who speak differently. So ‘language borrowing’ occurs.

- Sound changes are not random, they occur in a predictable way, which is how we’re able to reconstruct dead languages

Chapter Three: Language and Time 1

The Last Speakers of Proto-Indo-European

- Very few natural languages remain unchanged after 1000 years to be considered the same language.

- like the English example. It’s basically not intelligible for us.

- natural language = those that are learned and spoken at home

- Morris Swadesh was a linguist who developed a ‘resistant’ word list, which is a list of vocabulary that tends not to be replaced in most languages, or at least takes a long time to be replaced

- i.e. these are largely the ‘unique’ words in that language

- for example, English has borrowed more than 50% of its general vocab from Romance languages, mainly French (this is due to French Norman invaders having an influence on English) and Latin (due to centuries of Latin being used in technical, professional, court, and school settings)

- Only 4% of English’s CORE vocab has been borrowed. Meaning it has stayed true to its Germanic roots

- Swadesh compared old and new phases of languages and found that the average replacement rate for a thousand years in the CORE vocab was 20%.

- if more than 10% of the core vocab is different between 2 dialects, it means they are mutually unintelligible or at least close to it, and therefore they are distinct languages. - p. 41

- this means that in a thousand years time, most languages today will be incomprehensible to people in that future time

- Swadesh’s theory is not perfect. Icelandic has a replacement rate of 3-4% per thousand years, so it does not fit well into his theory.

- we don’t know how long Proto-Indo-European existed as a language, but a safe assumption would be 2000 years - p. 42

- reasons for this are on page 39-42

- The next question is, when did PIE die off as a language?

Death of PIE & Anatolian Languages

- we can determine terminal date of PIE by investigating birth of its first daughter

- Oldest daughter of PIE was Anatolian. It had 3 stems: Hittite, Luwian, and Palaic. All 3 are extinct - p. 43

- we have Hittite and Luwian texts going back to 1650 BC

- Local names in Kanesh Karum (a Hittite city) were Hittite or Luwian, with the earliest records being from 1900 BC

- Hittite and Luwian were sister languages in 1400 BC, the same way Irish and Welsh are. Common origin of Irish and Welsh is 2000 years ago, which places Proto-Anatolian to about 3400 BC. - p. 46

- In between PIE and Proto-Anatolian is “pre-Anatolian” which is an evolutionary stage between the two former ones

- Hittite has a consonant, a laryngeal sound, that other Indo-Euro languages lack. This most likely means that the Anatolian languages branched off from PIE very early on

- Hittite is very grammatically different from other Indo-Euro languages:

- it only has present and paste tense

- only has animate and neuter (no masc/fem)

- lacks a ‘dual’ case

- The fact that Hittite is so grammatically different led some experts to believe it’s not a daughter of PIE at all

- There’s a hypothesis that Hittite is “Indo-Hittite”, which states it didn’t come from PIE, but rather it came from Indo-Hittite, which produced both PIE and Anatolian, which makes them cousins, not mother and daughter - p. 47-48

- The author prefers to call this “Indo-Hittite” group “Archaic PIE” instead

- The reasonable time when Pre-Anatolian separated from Archaic PIE is around 4000BC - p. 48

- the window is 4500 to 3500BC, which is the absolute latest window where pre-Anatolian could’ve separated from archaic-PIE, so it could’ve been even earlier than that

- Using evidence about the Anatolian languages cannot provide us with an accurate death date for PIE given how much controversy & evidence exists that Anatolian might not even be a daughter of PIE, but rather a cousin

Death of PIE & Greek / Old Indic

- The Greek language is Indo-Euro and about the same age as Hittite.

- Greek was the language of the warrior kings who ruled Greece beginning in 1650 BC, they were called the Mycenaean civilization - p. 48

- We have tablets dating back to 1450 BC written in Greek, not proto-Greek

- We don’t know how they got there, or what happened before 1650 BC. The Greek sort of just appeared out of nowhere in 1650 BC

- Greek was an intrusive language in the Greece region. Other non-Greek languages were being spoken before the Mycenaean age

- Old Indic is the language of the Rig Veda, written in 1500 BC in the Punjab region - p. 49

- The actual teachings of the Rig Veda, like the deities, moral concepts, etc, first appeared in writing in northern Syria

- Old Indic is the authors term for the oldest branch of the Indic branch

- Indo-Iranian is right below Indo-European. Indo-Iranian produced 2 branches, Iranian and Indo-Aryan, but the author calls Indo-Aryan “Old Indic” because they were all Aryan anyways - p. 49

- The Mitanni dynasty ruled Syria during the time of the Rig Veda writing, they spoke Hurrian, a non-Indo-Euro language (it is related to the Caucasian languages) - p.49

- when one became King, they adopted an Old Indic name, even though they spoke Hurrian… this is interesting considering Old Indic is Indo-Aryan… were the Hurrian ruling class Aryan?

- The Mitanni texts prove that the Old Indic language existed by 1500 BC and that the religion pantheon and moral beliefs of the Rig Veda existed during that time as well - p. 50

- IMO this indicates Old Indic is a lot older than 1500 BC

- the reason why the Mitanni kingdom used Old Indic terms is not known, but a good guess is that the kingdom was founded by Old Indic speaking mercenaries, who usurped the throne from native Hurrians. So their kingdom was very Hurrian with some Old Indic elements. - p. 50

- In conclusion, we can safely say that by 1500 BC, PIE has branched off into at least 3 groups:

- Old Indic

- Mycenean Greek

- Anatolian

Death of PIE - Conclusion

- from the perspective of Mycenean Greek, we can place the death date of PIE at about 2400-2200 BC - p. 51

- this is because Greek is a language isolate, it has no sisters. It derived straight from Proto-Greek which is the daughter of PIE

- from the perspective of Old Indic, it’s more complicated because she has a sister, “Avestan Iranian” (this is the term author uses for the branch right below Indo-Iranian)

- Indo-European → Indo-Iranian → Iranian / Avestan Iranian, and Old Indic

- Since Old Indic was established in 1500BC, Indo-Iranian must date back to at least 1700BC, Proto-Indo-Iranian must date to at least 2000BC, pre-Indo-Iranian must have existed at the latest around 2500-2300BC at which point it died off

- So for Greek we have 2400-2200BC, and Old Indic we have 2500-2300BC

- Therefore, the death date of PIE was around 2500BC

- this means that by 2500BC, PIE has fragmented into Anatolian, Pre-Greek, and Pre-Indo-Iranian, with the original PIE being a dead language

- Did other daughters of PIE exist in 2500BC? Yes - p. 57

- Tocharian, Celtic, and Italic most likely branched off around or before 2500BC

- Germanic could’ve also, or it was later, around 2000BC

- Any Indo-European language that evolved after 2500BC did not evolve directly from PIE, but rather from one of PIE’s daughters

Chapter Four: Language and Time 2

Wool, Wheels, and Proto-Indo-European

- Now we move to the question of when was PIE born? When did it start being spoken as a language? We can answer this question with a high degree of accuracy due to vocabulary - p. 59

- Woven wool textiles and wheeled vehicles did not exist before 4000 BC. They might’ve not even existed before 3500BC. PIE is full of vocab for these things. Therefore PIE must have been spoken after 4000-3500BC

- the rest of this chapter goes into details on sheep and wheels

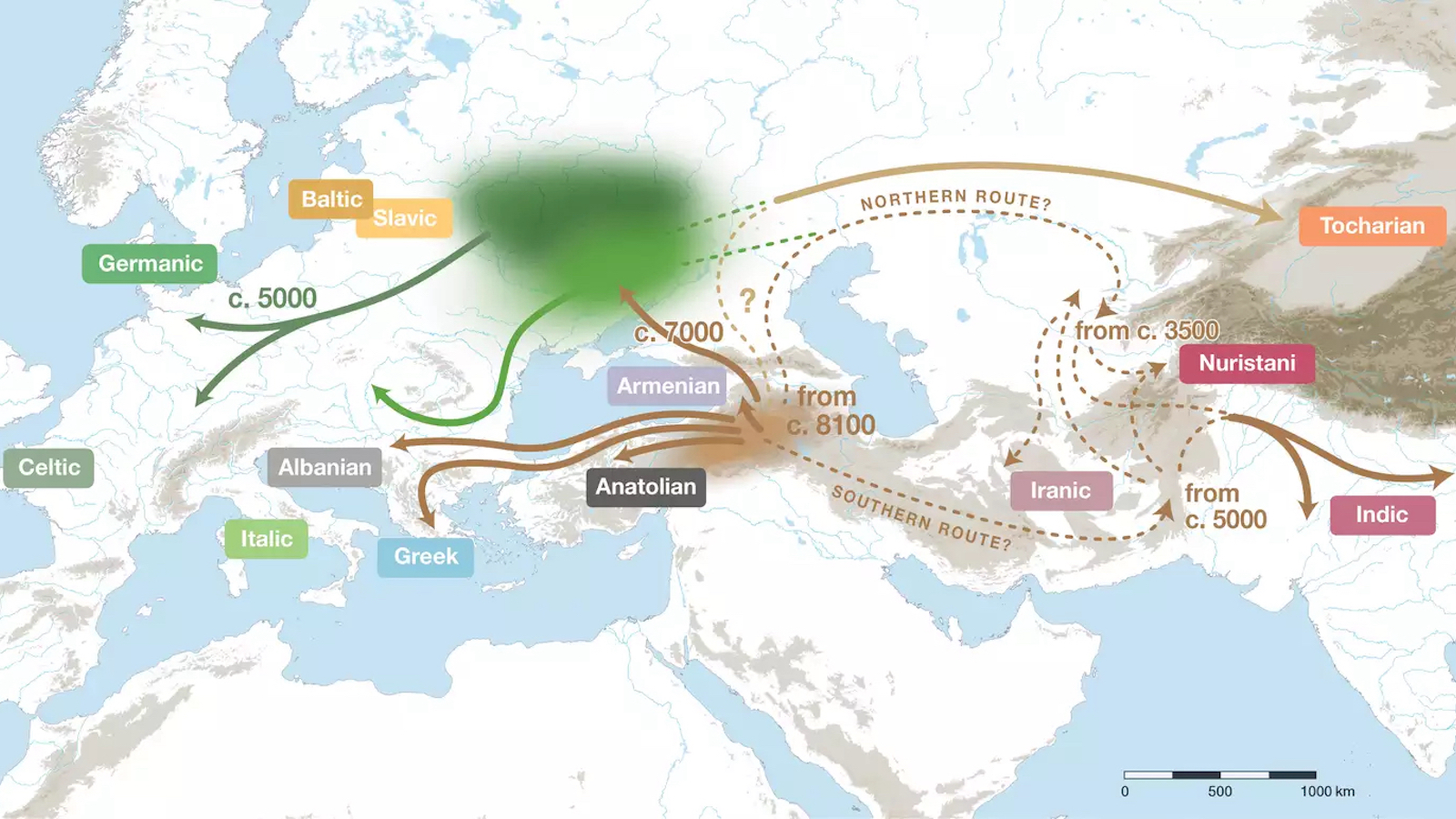

- to conclude the timing and dates of it all:

- Archaic PIE was spoken before 4000BC (partly preserved in Anatolian)

- early PIE was spoken between 4000-35000BC (partly preserved in Tocharian)

- late PIE was spoken between 3500-3000BC, which is the source of Italic and Celtic

- Pre-Germanic split occurred 3300BC

- Pre-Greek split occurred 2500BC

- Pre-Baltic split from pre-Slavic and other northwestern dialects about 2500BC

- Pre-Indo-Iranian developed from northeaster dialects between 2500-2200BC

- Now that timing is settled, the next question to tackle is WHERE PIE was spoken

Chapter Five: Language and Place

The Location of the Proto-Indo-European Homeland

- we can determine the location of the PIE homeland by examining the vocabulary of PIE

- this chapter goes over some of the hypothesis experts have as to where the PIE homeland was located.

- opinions include Caucasus, Anatolia, Armenia, etc

- the author comes to the conclusion that the homeland of PIE was located west of the Ural mountains, between the Urals and the Caucasus in the steppes of eastern Ukraine and Russia (the Pontic-Caspian region) - p. 99

- The heart of the PIE period was between 4000-3000BC, with the late phase ending by 2500BC, and an early phase going back to 4500BC

- this location is also supported by archaeological findings from that area

- page 100 has a useful graph

Chapter Six: The Archaeology of Language

- this chapter focuses on bridging the gap between language and archaeology, a gap which most archaeologist believe shouldn’t be bridged. The next chapter (and next part) of the book focuses on archaeology which is why this chapter is necessary - p. 101

- So how did PIE languages takeover? Likely, PIE people immigrated to these new lands like Europe, and brought with them their language, culture, rituals, etc. They became the leaders of these places which allowed them to influence the native people - p. 118

- interesting thing about Pathans and Baluchi on page 119

Part Two: The Opening of the Eurasian Steppes

- while part 1 focused on language of Indo-Europeans, this part focuses on the archaeology of Indo-European origins

Chapter Seven: How to Reconstruct a Dead Culture

- the rest of the book is on Part Two

- this chapter is just an introduction to Part 2 of the book.

Chapter Eight: First Farmers and Herders

The Pontic-Caspian Neolithic

- The Indo-European creation myth has been passed down to the cultures of her daughter languages - p. 134

- PIE mythology was the worldview of a male-centered, cattle-raising people

Chapter Nine: Cows, Copper, and Chiefs

- old Europe (pre Indo-Euro) was famous for its goddesses. Households had broad-hipped female figures. - p. 162

- this chapter focuses on investigating the cultures of the steppe/Caucasus/eastern Russia region before PIE

- basically all the graves that they’ve dug up that date to 5000BC are stained with ochre

Chapter Ten: The Domestication of the Horse and the Origins of Riding

The Tale of the Teeth

- this chapter is all about horses and their domestication

- horses were not originally domesticated for riding or transportation, they were actually domesticated for the purpose of meat - p. 200

- in winter times, cattle and sheep easily die off, but horses survive because they use their hooves to move snow and break ice so they can eat the grass beneath it. Cattle don’t do that, and sheep use their noses to move snow, which causes them to get sick and die, they also can’t break ice.

Chapter Eleven: The End of Old Europe and the Rise of the Steppe

- the peak of old Europe was 4300-4200 BC. - p. 225

- we can see the highest amount of gold ornaments in the graveyards of Europe dating to this period

- there was a sudden culture shift around 4200-3900BC. This replaced the culture of Old Europe with a new one. Around this time there was a small climate crisis which is one of the reasons for this cause it led to soil erosion, agricultural failures, etc, - p. 227-228

- in the annotations it says that climate couldn’t have been the real cause, rather warfare is more likely. Evidence points to a sudden and abrupt change, so warfare makes more sense

- large scale wars were most likely not a thing. There were no army’s. Raiding was probably a thing and happened

- cattle raiding was encouraged by Indo-Euro beliefs and rituals - p. 239

- it was very common for the people of Old Europe and Indo-Euro to bury their dead with some possessions, especially the richer folk. They were buried with ornaments, bracelets, etc, made of gold and copper

- to conclude, the sudden abandonment of settlements in old Europe at around 4000BC was party caused by the climate change that caused hardship with food production, but we also have evidence of massacres, so there were definitely some conflicts as well - p. 258-259

- this event most likely is what led the pre-Anatolians to break off from PIE to inhabit Europe after leaving the Steppe region - note 54

- pre-Anatolian languages were probably introduced to the lower Danube valley and Balkans around 4200-4000BC - p. 262

Chapter Twelve: Seeds of Change on the Steppe Borders

Maikop Chiefs and Tripolye Towns

- this chapter discusses the influence of early Mesopotamian urban civilizations on steppe societies, and vice-versa

- first contact between Mesopotamian civilizations and steppe people occurred around 3700-3500BC - p. 263

- this contact caused a social and political transformation that we can see through the Maikop culture of the North Caucasus

- The Tripolye towns, at around 3500BC, were the largest human settlements in the world at that time. Eventually they all collapsed. - p. 264

- The Volga-Ural steppe people migrated to the Altai mountains in Kazakhstan in 3500BC. This created the Afanasievo culture, which spoke the first Tocharian language. - p. 264

- 3700-3500BC is when the first cities of Mesopotamia emerged - p. 282

- A Maikop chieftain was buried wearing Mesopotamian symbols of power, like the lion paired with the bull. This is definitely from Mesopotamian influence cause the Caucasus had no lions. - p. 289

- Mesopotamian traders travelled to Anatolia and Caucasus, which is how the influence took place. - p. 294

- The Maikop culture collapsed when trade stopped because the Mesopotamians were having internal issues - p. 295

- the wagon was most likely a tool that was brought by the Mesopotamians to the Caucasus - p. 295

Chapter Thirteen: Wagon Dwellers of the Steppe

The Speakers of Proto-Indo-European

- The chapter introduces the Yamnaya culture, the first speakers of PIE. The previous few chapters have all been on cultures before PIE was a thing

- as the steppe people got wagons, frequent migrations and nomadic lifestyle became more common. This led to land disputes and the need to create rules for what defined an acceptable move. Those who participated in such rules were part of the Yamnaya culture, while those who didn’t were deemed cultural “others”. - p. 300

- the Yamnaya people became known to live off wheels, whether it be wagons for slow transport, or horses for fast transport - p. 302

- Western Indo-European was much more female-centered in its mythologies, while Eastern Indo-Euro (Indo-Iranian) was more male-centered - p. 305

- the first pastoral economy based on mobility was an invention of the Yamnaya - p. 322

- The Yamnaya people prayed to the Sky Father and were a patriarchal society - p. 328

Chapter Fourteen: The Western Indo-European Languages

- how does a language get adopted? The social group that the old language was a part of gets stigmatized, while the social group the new language is a part of gets emulated and admired - p. 341

- a language gets emulated and admired by status enhancement

- factors that enhanced the status of the Yamnaya people, p. 341:

- they were horse breeders and knew it better than anyone else. They had the best and strongest horses

- they were horseback riders which allowed them to travel and migrate

- they believed in the sanctity of oaths

- they developed a political infrastructure to manage migratory behavior

- they had an elaborate political theater around their funerals

- overall, the spread of Indo-European languages was most likely not an invasion or militaristic, rather it was the opposite

Chapter Fifteen: Chariot Warriors of the Northern Steppes

- the people who wrote the Avesta and Rid Veda self identified as Aryan. They are the original Indo-Iranians - note #3

- The Sintashta people rode chariots to war. They were frequently buried with weapons so they were certainly involved with war. This is about 2100BC

- Chariots were invented in the steppes, then introduced to the Near East through Central Asia - p. 403

- the funeral rituals of the Sintashta people (located in the Steppe) closely resembled the rituals described in the Rig Veda - p. 408

- The language Indo-Iranian, parent to both Old Indic and Iranian Avestan, was probably spoken during the Sintashta period, 2100-1800BC - p. 408

- Archaic Old Indic and Iranian Avestan probably emerged as separate languages around 1800-1600BC

- The Rig Veda and the Avesta both agree that the essence of their shared parental Indo-Iranian identity was linguistic and ritual, not racial - p. 408

- you were an Aryan if you performed rituals the correct way

- Therefore, the origin of the original Indo-Iranian people was most likely the Sintashta people of the Steppe - p. 409

Chapter Sixteen: The Opening of the Eurasian Steppes

- talks a lot about how horses and chariots were introduced to the Near East

- people of the steppes migrated south towards Afghanistan. We can see influence of steppe culture in Bactria through pottery designs.

- there was lots of trade between people from the south (Tajikistan, Afghanistan) and the steppe people. A lapis lazuli bead from Afghanistan was found in a Sintashta grave - p. 434

- the Old-Indic speaking people who invaded the Punjab and wrote the Rig Veda most likely originated from Iran and Afghanistan - p. 454

- Iranian dialects probably developed in the Northern Steppes, while Old Indic languages developed in the contact zone in Central Asia - p. 454

- the Rig Veda, written in Old Indic, contained 383 non-Indo-Euro loan words. Many of these words were already loaned into common Indo-Iranian, so we see that Old Indic and/or Iranian Avestan had them too - p. 455

Chapter Seventeen: Words and Deeds

- this chapter is a conclusion of the book

Main Idea of the Book

- this books aims to provide answers to some of the most debated questions in Indo-European studies:

- when was PIE spoken? Who spoke it? And where was it spoken?

- when were the children languages spoken?

- it covers two main parts: linguistics in part one and archeology in part two

Reflections

The archeology part of the book wasn’t too interesting for me. It went too in-depth and I simply wasn’t interested in that level of detail.

There also wasn’t any discussion on the Fertile Crescent or Anatolia homeland theories of PIE origins.